Sitting Tolerance vs Sitting Time

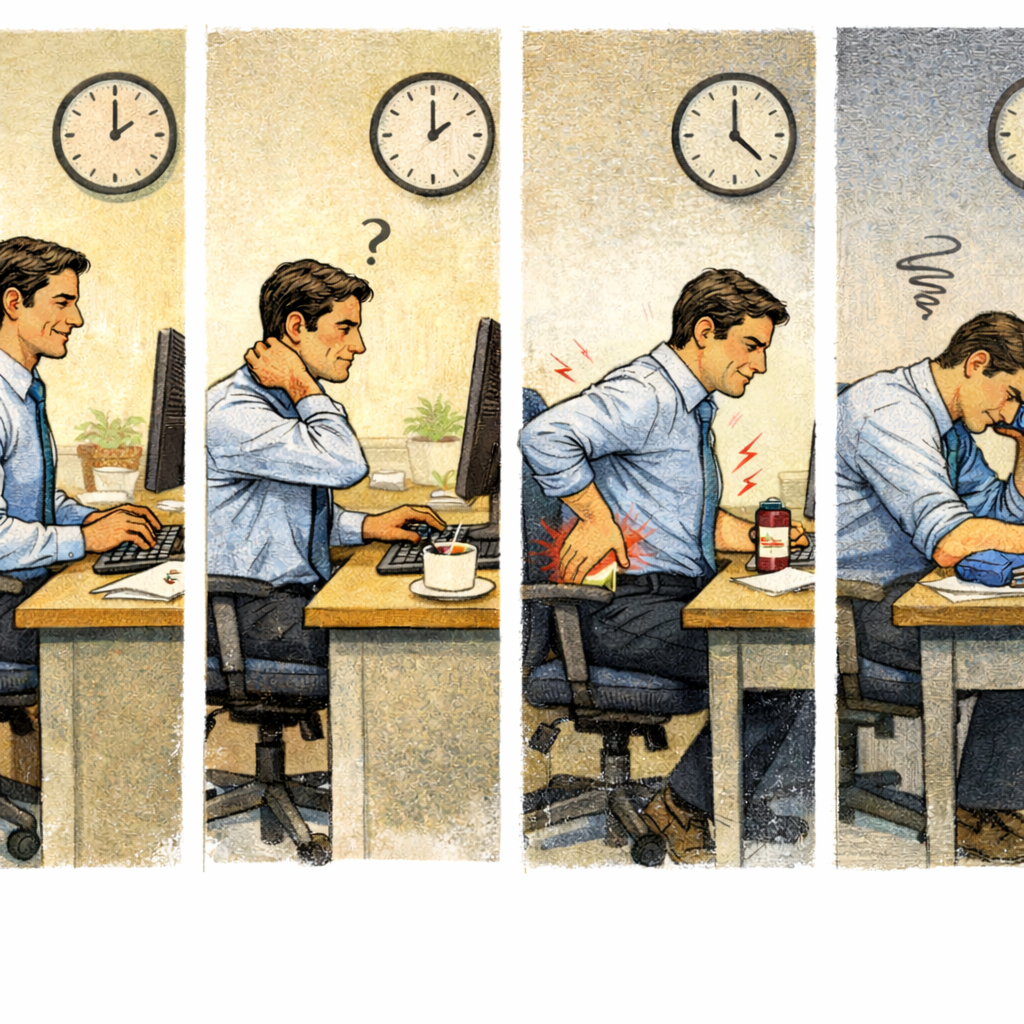

For decades, the prevailing narrative around desk work has been simple: sitting too long is harmful. Movement, of course, plays an important role in overall health. But focusing on time alone overlooks a more fundamental factor in why sitting becomes uncomfortable for so many people.

The real determinant of discomfort is not how long you sit—it’s how well your body tolerates sitting.

Sitting tolerance refers to your body’s ability to remain seated without excessive strain, fatigue, or pain. This tolerance varies widely from person to person. Some individuals can remain seated for extended periods with little issue, while others begin to experience discomfort within minutes. The difference is rarely a matter of discipline, posture awareness, or physical strength.

Instead, it comes down to support.

When the body lacks adequate structural support, muscles are forced to compensate. They remain subtly engaged to hold posture, stabilize the spine, and manage pressure that should be distributed by the chair and surrounding environment. Sitting for prolonged periods without proper support can increase strain not only on the back and neck but also on the legs and other muscle groups. The legs play a key role in maintaining posture, and lack of support can lead to discomfort or fatigue in the legs during extended sitting. Over time, this added demand reduces tolerance and accelerates fatigue—even during relatively short periods of sitting.

Understanding sitting tolerance shifts the conversation away from blame and toward design. When support is appropriate, the body works less to remain upright, discomfort is delayed or eliminated, and sitting becomes a sustainable position rather than a source of strain.

In the sections that follow, we’ll explore what sitting tolerance truly means, why it declines, and how the right support can dramatically change how desk work feels—regardless of how many hours you spend seated.

Sitting Time Isn’t the Problem—Sitting Tolerance Is

Sitting tolerance describes how much seated load your body can manage before discomfort begins. It is not a fixed trait, nor is it determined solely by the number of hours you spend in a chair. Instead, it reflects how efficiently your body is supported while sitting and how much muscular effort is required to maintain alignment.

This is why two people can sit for the same duration and experience entirely different outcomes. One may complete the workday feeling relatively comfortable and focused. The other may finish with lower back pain, tight hips, or a deep sense of physical fatigue that lingers long after standing up.

The difference lies in how much work the body is being asked to do while seated.

When sitting is unsupported, the body absorbs continuous load through muscles, joints, and spinal discs. Stabilizing muscles remain active to prevent collapse, posture requires constant low-level correction, and pressure accumulates in areas not designed to carry it for extended periods. As this load builds, tolerance decreases. Even short periods of sitting can begin to feel heavy, restrictive, or uncomfortable.

Viewing sitting through the lens of tolerance shifts the focus away from arbitrary time limits. Rather than asking, “How long have I been sitting?” a more meaningful question becomes:

“How well is my body being supported while I sit?”

When support is appropriate, the body expends less effort to remain upright, pressure is better distributed, and sitting becomes a position that can be sustained—regardless of duration.

Why Sitting Can Feel Physically Exhausting

Sitting is often perceived as a resting position—something the body settles into with minimal effort. In practice, however, unsupported sitting is an active task. When adequate ergonomic support is absent, the body must generate its own stability to remain upright.

In these conditions, several muscle groups remain continuously engaged. The core stays partially contracted to prevent collapse through the torso. The hip flexors remain shortened and under constant tension, limiting relaxation through the pelvis. Meanwhile, the muscles of the lower back work persistently to stabilize the spine and control small, repetitive shifts in posture.

Although these contractions are subtle, their cumulative effect is significant. Over time, this sustained muscular effort leads to core fatigue from sitting, even though the body appears still. This is why long periods of desk work can feel surprisingly draining—fatigue builds not from movement, but from continuous compensation.

Importantly, this type of exhaustion is often misunderstood. It is not a reflection of poor fitness or insufficient strength. Rather, it is a signal that the body is absorbing load that should be managed by external support. When furniture fails to provide structure, muscles are forced to take over, turning sitting into a physically demanding activity.

Incorporating short bouts of exercise or movement throughout the day can help counteract the fatigue caused by prolonged unsupported sitting.

With proper support in place, these muscles are no longer required to work continuously, allowing sitting to return to what it should be: a stable, low-effort position that preserves energy rather than depleting it.

“But I Have Good Posture”—Why Alignment Alone Isn’t Enough

Posture awareness is valuable, but good posture on its own does not guarantee comfort. Many people who are attentive to alignment still experience sitting pain, stiffness, or fatigue—often because posture is being actively maintained rather than naturally supported.

When posture is held, it relies on continuous muscular engagement. The frequent cue to “sit up straight” encourages the body to recruit stabilizing muscles throughout the day. While this may improve appearance or alignment in the short term, the sustained effort required to maintain it can gradually increase strain. Over hours of sitting, that effort accumulates, leading to fatigue even in individuals with strong posture habits.

The distinction is important:

-

Held posture: Muscles remain active to maintain alignment, increasing effort over time

-

Supported posture: External support maintains alignment, allowing muscles to relax

Without adequate lumbar and pelvic support, the spine lacks a stable foundation. Even well-intentioned posture correction then becomes a form of low-grade exertion rather than a solution. Over time, this can contribute to discomfort in the lower back, hips, and core.

This is why effective ergonomic tools are not designed to force posture or impose rigidity. Instead, they work by reducing the muscular cost of staying upright, allowing alignment to occur with less conscious effort. When posture is supported rather than enforced, sitting becomes more sustainable and far less demanding on the body.

Why Sitting Hurts More As You Get Older (and What That Actually Means)

Many people notice that sitting becomes less comfortable with age. Positions that once felt effortless may now lead to stiffness, fatigue, or discomfort far more quickly. This change is not unusual, and it does not indicate that pain is inevitable. Rather, it reflects a reduction in tolerance for unsupported positions over time.

As the body ages, tissues generally recover more slowly, joints become less adaptable to sustained load, and the margin for prolonged strain narrows. When sitting lacks adequate support, these age-related changes become more noticeable. Discomfort tends to appear sooner—not because the body is failing, but because it has less capacity to compensate for poor structural conditions.

This is where support becomes increasingly important.

Sitting tolerance can be thought of in the same way as endurance. When the body is properly supported, pressure is distributed more evenly across the pelvis and spine, stabilizing muscles are able to relax rather than brace, and sitting once again becomes a position that can be sustained comfortably.

How Support Increases Sitting Tolerance

Proper ergonomic sitting support reduces the amount of physical work your body must perform simply to remain seated. Instead of relying on continuous muscular effort to stabilize posture, the body is able to share load with the surrounding environment. This shift is what allows sitting tolerance to increase.

The most effective ergonomic setups focus on specific support zones that influence alignment, pressure distribution, and stability:

| Support Area |

Why It Matters |

|---|---|

| Lumbar (lower back) | Maintains the spine’s natural curve, reducing disc compression and minimizing the need for constant muscular bracing |

| Seat & pelvis | Distributes body weight evenly, supports neutral pelvic positioning, and helps prevent slouching or forward collapse |

| Feet & floor contact | Enhances overall stability and reduces compensatory strain throughout the spine and hips |

When these areas are properly supported, muscles are no longer required to replace structural support. Instead, they can perform their intended role—assisting movement and responding to change, rather than holding the body upright for hours at a time.

Targeted ergonomic tools are designed to provide this kind of structural assistance without forcing rigid posture. For example, the Serenform Atlas Lumbar Pillow supports the natural curvature of the lower back, allowing the spine to remain aligned with minimal effort. Similarly, the Serenform Summit Seat Cushion improves pelvic positioning and pressure distribution, creating a more stable foundation for sitting.

Used together, these supports significantly reduce unnecessary muscular effort. The result is increased sitting tolerance, less fatigue, and a seated position that feels calmer, lighter, and far more sustainable throughout the day.

Combining ergonomic support with regular moderate activity, such as brisk walking or cycling, can further improve comfort and reduce health risks associated with sitting.

Supported Sitting vs Unsupported Sitting: What Changes in Your Body

The difference between supported and unsupported sitting is not subtle. When adequate support is introduced, the way the body manages load, alignment, and effort changes immediately. These changes explain why some seating setups feel sustainable, while others become exhausting over time.

When sitting is unsupported, the body must generate its own stability. Core muscles remain continuously engaged, spinal structures absorb uneven pressure, and posture requires frequent correction. This ongoing effort accelerates fatigue and reduces sitting tolerance, even during relatively short periods of desk work.

By contrast, supported sitting allows the environment to share the load. External support maintains alignment and distributes pressure more evenly, reducing the need for constant muscular bracing.

| Unsupported Sitting |

Supported Sitting |

|---|---|

| Continuous core engagement | Reduced muscle activation |

| Increased spinal compression | More even pressure distribution |

| Faster onset of fatigue | Extended sitting tolerance |

| Frequent posture correction | Natural alignment with less effort |

The body is not designed to brace itself throughout the workday. When it is forced to do so, fatigue and discomfort are inevitable. Support provides the structure that allows muscles to relax, joints to move less defensively, and posture to stabilize without constant conscious effort.

With proper support in place, sitting becomes less about endurance and more about efficiency—allowing the body to remain seated with significantly lower physical demand.

The Hidden Health Risks of Prolonged Sitting

While sitting is a common part of daily life, especially for children at school or during screen time, prolonged sitting can quietly lead to a host of health problems. According to Harvard Health Publishing, spending long periods in a seated position is associated with increased risks of neck pain, joint pain, and even heart disease. Poor sitting posture, often seen when children are hunched over a computer screen or slouched in a chair, can further contribute to discomfort and long-term issues with the spine and spinal discs.

Children, particularly those with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), may be especially vulnerable to the negative impact of prolonged sitting. For many children with ASD, challenges with sensory processing and body awareness can make it harder to engage in regular physical activity or manage body weight. This can lead to a cycle where sitting time increases, physical activity decreases, and health risks accumulate.

The effects of too much sitting go beyond physical pain. Extended periods spent watching television or using computers can negatively affect a child’s behavior, social life, and communication skills. Social interaction may decrease, and children may find it harder to develop essential life skills. A lack of movement throughout the day can also contribute to higher blood pressure and poor regulation of blood sugar, further increasing the risk of chronic health problems.

Healthcare professionals, including occupational therapists, recommend a proactive approach to reduce these risks. Encouraging children to use a standing desk, take regular breaks to stand and move, or engage in sensory activities can help improve sitting tolerance and overall health. Simple changes—like using a therapy ball for short periods, incorporating light activity such as stretching or walking, and ensuring the work surface and computer screen are at eye level—can make a significant difference.

Creating a distraction-free environment is also key. When children are supported to focus on different activities and given opportunities for more movement, they are less likely to experience the negative effects of prolonged sitting. Parents and caregivers can play a vital role by modeling good posture, providing supportive chairs, and encouraging regular physical activity throughout the day.

Ultimately, reducing the health risks of prolonged sitting is about more than just limiting sitting time. It’s about helping children develop the life skills they need to manage their bodies, engage in a variety of activities, and find support when needed. By prioritizing movement, proper posture, and a supportive environment, parents and caregivers can help children achieve better health, improved sitting tolerance, and a more active, connected social life.

You Don’t Need to Sit Less—You Need to Sit Smarter

Regular movement and posture changes are important for overall health, but they are often misunderstood as solutions to sitting-related discomfort. While movement breaks provide short-term relief, they cannot compensate for a sitting setup that lacks proper support.

When the seated environment is poorly designed, increasing time spent standing does not resolve the underlying issue. Stretching may temporarily reduce stiffness, but it does not address the structural demands placed on the body while seated. Likewise, posture reminders can improve awareness, yet they rely on sustained effort rather than reducing the load that creates fatigue in the first place.

Smarter sitting focuses on environmental design, not constant self-correction. By adjusting how the body is supported, the physical work of sitting is shared between the body and its surroundings. This reduces unnecessary muscular effort and allows alignment to occur naturally.

When support is properly integrated, sitting no longer feels like something to endure between breaks. Instead, it becomes a position the body can maintain with less strain, greater comfort, and improved focus throughout the day.

Rebuilding Sitting Tolerance Starts With the Right Support

For many people, extended desk work is a practical reality rather than a choice. In this context, the solution to sitting-related discomfort is not eliminating sitting altogether, but increasing the body’s capacity to tolerate it.

This is why Serenform approaches ergonomic design as a system rather than a collection of isolated products. The Desk Comfort Bundle combines targeted lumbar and seat support to address the most common sources of sitting fatigue simultaneously. By supporting both spinal alignment and pelvic positioning, the body is no longer required to compensate for missing structure.

When proper support is restored, several important changes occur. Muscles are able to relax instead of bracing throughout the day. Pressure is distributed more evenly across the pelvis and spine. As a result, sitting tolerance improves naturally, without the need for constant posture correction or conscious effort.

Effective ergonomic support does not force the body into position or demand ongoing vigilance. It simply provides structure where it is needed most, allowing the body to settle into a more efficient, sustainable seated posture.

Conclusion: Sitting Isn’t the Enemy—Unsupported Sitting Is

Sitting, in itself, is not inherently harmful. The discomfort and fatigue commonly associated with desk work arise not from sitting alone, but from sitting without adequate support. When the body is left to manage posture and stability on its own, even brief periods of sitting can become uncomfortable and demanding.

When proper structure is restored, the experience of sitting changes. Muscular effort decreases, pressure is distributed more evenly, and the body no longer needs to brace against the environment. Sitting begins to feel lighter, calmer, and far more sustainable—regardless of how many hours the workday requires.

Rather than focusing solely on duration, it is more productive to reconsider the conditions under which you sit. Ask not how long you have been seated, but whether your body is being adequately supported while you are there.

When support is present, sitting stops being something you endure or push through. It becomes a position your body can tolerate comfortably—allowing you to work with greater ease, focus, and long-term well-being.