Core Fatigue Sitting: Why Your Core Is Overworked at Your Desk

If you regularly reach mid-afternoon feeling physically drained, achy, or unusually fatigued—despite spending most of the day seated—this experience is both common and explainable. A desk job often leads to this type of fatigue, as it requires long periods of sitting with minimal movement.

For many desk-based professionals, sitting is not a passive or restorative posture. In practice, it places sustained demands on the body that often go unnoticed. One of the primary reasons is subtle but significant: your core muscles are working continuously while you sit, compensating for a lack of structural support. Sedentary behaviour, such as prolonged sitting during work or daily routines, further contributes to this problem by reducing overall muscle activation and functional capacity.

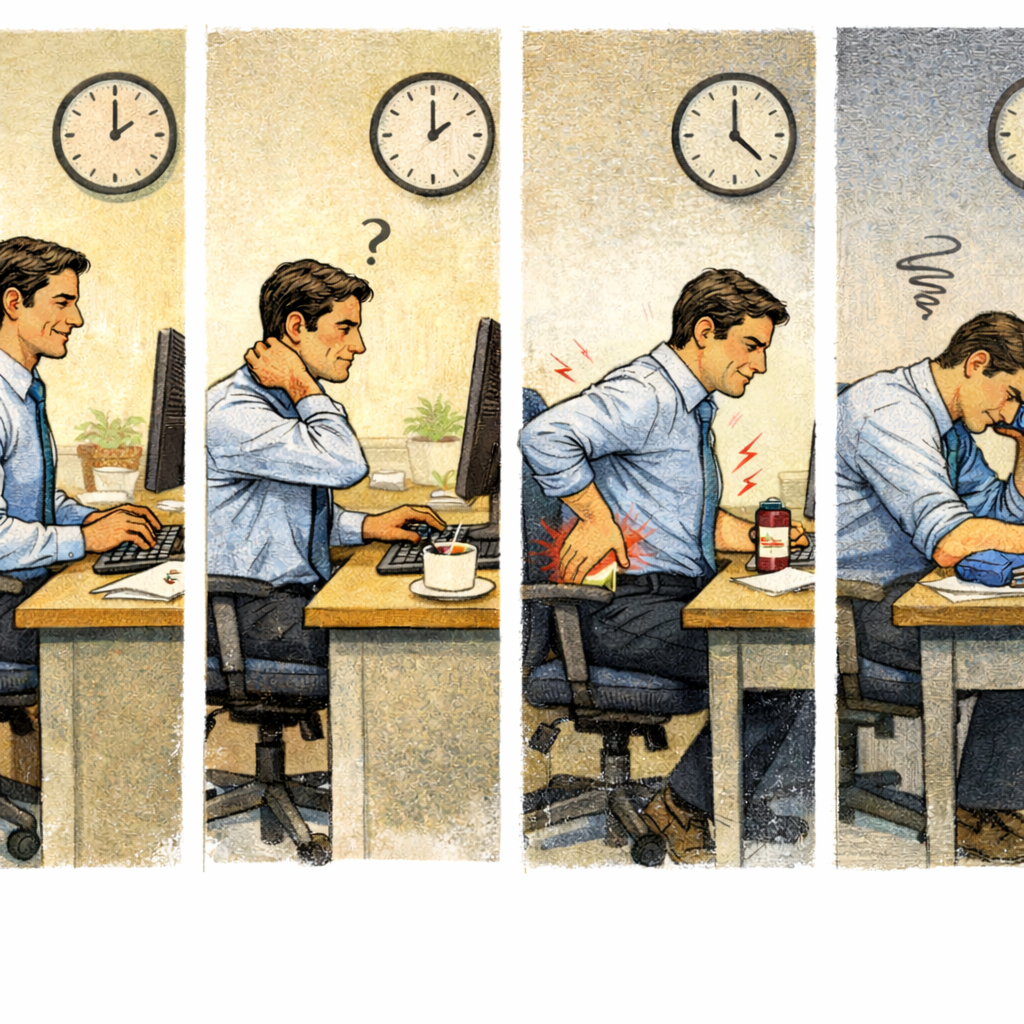

This ongoing, low-level muscular engagement may not feel intense in the moment, but over the course of several hours it accumulates. The result is familiar to many: afternoon fatigue, increasing lower back discomfort, and a gradual loss of upright posture as the day progresses. This process leads specifically to fatigued trunk muscles, which impairs core stability and postural control—not just a general sense of tiredness.

Understanding why this happens is the first step toward addressing it effectively. When the source of the strain is clear, it becomes easier to identify solutions that reduce effort rather than asking the body to endure it.

Sitting Shouldn’t Feel This Tiring

Sitting is generally understood as a low-effort posture—one that allows the body to rest while the mind works. Yet for many people, a full day at the desk results in more physical fatigue than hours spent standing or moving.

When you feel tired from sitting all day, the cause is rarely a lack of fitness, discipline, or age-related decline. More often, it’s a sign that your body is compensating for missing or inadequate support within your seated setup.

In the absence of proper structural support, the body relies on muscular effort to maintain stability. The core, in particular, becomes responsible for holding the torso upright, resisting collapse, and protecting the lower spine. This continuous engagement may be subtle, but sustained over several hours, it creates meaningful physical load. This continuous engagement in the sitting position leads to muscular fatigue, as the trunk muscles are forced to work for prolonged periods without adequate support.

This is why sitting can feel surprisingly exhausting. It is not a matter of inactivity or laziness—it is a matter of load being carried by muscles that were never intended to perform that role for extended periods.

Why Your Body Wasn’t Designed to Hold Itself Up All Day

When you are standing or moving, your body relies primarily on its skeletal structure for support. Bones and joints are designed to stack efficiently, allowing weight to be transferred through the body with minimal muscular effort. Muscles engage as needed, then relax, creating a natural rhythm of activation and recovery.

Prolonged sitting disrupts this balance.

In a seated position:

-

Overall movement is significantly reduced

-

Natural skeletal alignment is altered

-

Stabilizing muscles remain engaged for extended periods

-

Body weight is distributed differently, which changes how muscles engage to support the spine

Without frequent movement or adequate external support, muscles—particularly those responsible for core stability—are required to stay active far longer than they were designed to. When core muscles fatigue, the body increasingly relies on passive structures such as ligaments and spinal discs to maintain posture, which can lead to poor spinal alignment and discomfort. This sustained activation transforms sitting into a static task rather than a resting posture.

Over time, this leads to sitting posture strain. Not because sitting itself is inherently harmful, but because unsupported sitting shifts structural responsibility away from the skeleton and onto muscles that are ill-suited for continuous load-bearing, eventually forcing passive structures to compensate.

This is where fatigue begins to accumulate and discomfort gradually emerges—often well before the end of the workday.

What Your Core Muscles Are Actually Doing While You Sit

It’s a common assumption that sitting allows the core to fully relax. In practice, that is rarely the case—especially in work environments where seating lacks proper support.

When lumbar support is missing or insufficient, the body relies on subtle muscular engagement to maintain upright posture. Research measuring trunk muscle activity, often using electromyography (EMG), shows that the core muscles—including deep stabilizers like the transversus abdominis—activate continuously to:

-

Prevent the torso from collapsing forward

-

Protect the lower spine from excessive strain

-

Maintain balance and stability over the hips

This type of core engagement while sitting is not forceful or immediately noticeable. Instead, it operates at a low level throughout the day. While each moment of activation may feel insignificant, the cumulative effect of sustained muscle engagement leads to fatigue over time.

The core is fundamentally designed to provide stability during movement—responding dynamically as the body shifts, bends, and rotates. It is not designed to function as a constant bracing system for prolonged, static postures.

The Hidden Cost of Prolonged Sitting Up Straight All Day

Posture guidance is often reduced to a simple instruction: sit up straight. While well intentioned, this advice overlooks how the body actually maintains alignment over time.

Attempting to hold an upright posture through muscular effort alone places a continuous demand on stabilizing muscles. Initially, this may feel manageable. However, as the hours pass, those muscles fatigue—especially when they are required to stay active without relief. Repeated muscle contraction, particularly in the core stabilizing muscles, accelerates the onset of fatigue.

In practice, the pattern often looks like this:

-

You consciously correct your posture and sit upright

-

Supporting muscles gradually tire

-

Posture begins to collapse

-

Discomfort and tension increase

-

You compensate by overcorrecting once again

This process can result in higher activation ratios in certain trunk muscles, such as the transversus abdominis and internal oblique, as the body tries to maintain posture. Rather than improving alignment, this repeated cycle produces posture fatigue. The body is forced to oscillate between effort and collapse, never achieving sustainable support.

When posture depends primarily on conscious effort instead of structural assistance, fatigue is inevitable. Over time, the body will choose relief over precision, even if that relief comes at the cost of discomfort later in the day.

Why Even a Strong Core Experiences Muscle Fatigue at a Desk

This is often unexpected, particularly for individuals who are physically active and maintain strong core musculature. Regular exercise, however, does not automatically protect against core fatigue from sitting. While muscle strength—such as that of the rectus abdominis—enables short bursts of force, even strong muscles can fatigue when required to maintain low-level activation for extended periods, highlighting the difference between strength and endurance.

The reason lies in the difference between strength and sustained load. Muscular strength reflects how much force a muscle can produce for short periods. Sustained, low-level demands—especially when there is little opportunity for rest—place a very different type of stress on the body.

A useful comparison is holding a light object at arm’s length for an extended time. Even though the weight is manageable, maintaining the position becomes tiring as minutes turn into hours. Sitting without adequate support creates a similar condition: a continuous, low-intensity demand with no meaningful recovery.

This is why even individuals with a strong core can experience discomfort and lower back pain during desk work. The issue is not a lack of fitness or capability. It is a mechanical mismatch between what the body is being asked to do and how it is supported while doing it.

How Poor Lumbar Support Forces Your Core to Compensate

This is where the role of seated support becomes especially important.

When proper lumbar support is absent, the body’s foundational alignment begins to break down. The pelvis tends to rotate backward, the natural curve of the lower spine flattens, and the torso loses its ability to remain balanced with minimal effort. As structural stability diminishes, spinal support is reduced, and the body instinctively responds by recruiting muscle to prevent collapse.

In this context, the core muscles are called upon repeatedly to do work they were never intended to sustain throughout the day. Rather than assisting posture, they are forced to replace missing support.

Over time, this pattern commonly leads to:

-

Increasing lower back pain by mid- to late afternoon

-

Fatigue in the core and hips

-

Greater difficulty maintaining an upright posture without conscious effort

Targeted ergonomic support restores the body’s natural structure, allowing weight to be distributed through the skeleton instead of relying on continuous muscular engagement. When the spine’s natural curve is supported, the core no longer needs to compensate simply to keep the body upright.

This is precisely the purpose of solutions such as the Serenform Atlas Lumbar Pillow—to support the lumbar spine in a neutral position, reduce unnecessary muscular workload, and allow the core to relax rather than overwork. Supported dynamic lumbar extension exercises can also help restore spinal support in desk workers by enhancing muscle activation and postural stability.

Effects of Muscle Imbalances You Didn’t Know You Had

Muscle imbalances are a hidden consequence of prolonged sitting that can quietly undermine your comfort and health. When you spend hours in a seated position, certain muscles—like the core muscles, including the transverse abdominis and internal oblique—can become underactive, while others, such as the hip flexors and quadriceps muscles, may tighten and overcompensate. This imbalance disrupts the natural support system for your lumbar spine, often leading to poor posture, muscle fatigue, and persistent back pain.

Over time, these imbalances can cause muscle stiffness and tension, especially in the lower back and legs. Tight quadriceps muscles and hip flexors can pull the pelvis out of alignment, making it even harder for your core to provide the stability your body needs. The result is a cycle of discomfort and fatigue that can be difficult to break.

The good news is that targeted strengthening exercises and core stabilization exercises can help restore balance. By focusing on the deep trunk muscles and incorporating physical activities that engage the core, you can alleviate muscle tension and reduce muscle fatigue. Stretching and foam rolling the hip flexors and quadriceps also play a crucial role in improving muscle balance and supporting a healthier, more comfortable posture—even during long hours at your desk.

Support vs Comfort: Why Softness Alone Isn’t Enough

Comfort is often equated with softness, but softness alone does not necessarily reduce physical strain. While a plush cushion may feel pleasant initially, it does little to address the structural demands of prolonged sitting.

Soft seating materials tend to compress over time. As they do, the pelvis loses stability, posture gradually collapses, and the spine drifts out of alignment. When this happens, the body once again relies on muscular effort to compensate for the loss of structure.

Effective ergonomic sitting support focuses on three essential principles:

-

Maintaining proper alignment

-

Distributing load evenly across contact points

-

Preserving the spine’s natural curves

A well-designed seat cushion, such as the Serenform Summit Seat Cushion, supports these principles by stabilizing the pelvis and reducing pressure at key points. By creating a more balanced seated foundation, it allows the spine to remain aligned with less conscious effort and less muscular strain.

True support does not require the body to work harder to maintain posture. Instead, it reduces unnecessary effort—allowing muscles to relax and function as intended throughout the day. Investing in a high quality ergonomic chair can further reduce the need for muscular compensation and help maintain proper posture over long periods of sitting.

What Proper Support Changes by Mid-Afternoon

When seated support is functioning as intended, the difference becomes most noticeable as the day progresses. Rather than accumulating strain, the body maintains stability with far less effort.

With proper support in place, many people experience:

-

Reduced tension in the lower back

-

More consistent, upright posture throughout the day

-

Less overall sitting fatigue

-

Improved concentration and mental clarity in the afternoon

Research has shown significant improvement in posture and comfort when proper support is used.

Instead of feeling physically depleted by mid-afternoon, the body is able to preserve alignment naturally. Muscular energy that was previously devoted to holding the torso upright can be redirected toward movement, focus, and sustained productivity.

This shift marks an important distinction. Rather than merely enduring the workday and pushing through discomfort, proper support allows sitting to become sustainable—supporting both physical comfort and long-term well-being.

These findings provide valuable insights for both individuals and organizations seeking to improve workplace health.

The Benefits of Microbreaks (and How to Take Them)

One of the simplest and most effective ways to combat the negative effects of prolonged sitting is to take regular microbreaks. These short breaks—just 5 to 10 minutes every 30 to 60 minutes—can make a significant difference in how your body feels by the end of the day.

Microbreaks give your core muscles a chance to relax and recover, helping to reduce muscle fatigue and prevent the build-up of tension. They also encourage better circulation and can boost your energy and productivity. During a microbreak, try standing up and stretching, taking a quick walk, or doing a few gentle movements at your desk. Even small actions, like rolling your shoulders, stretching your neck, or engaging your core muscles, can help reinforce good posture and alleviate the strain of prolonged sitting.

By making microbreaks a regular part of your routine, you can reduce the impact of sedentary behavior, support your physical well-being, and return to your work feeling refreshed and more focused.

Role of Physical Activity in Giving Your Core a Break

Regular physical activity is essential for giving your core muscles the support and recovery they need. When you move your body—whether through cardio, strength training, or flexibility exercises—you strengthen key muscles like the transverse abdominis, internal oblique, and erector spinae. This not only improves core stability but also helps reduce muscle tension and the risk of poor posture.

Physical activity breaks up sedentary behavior, which is a major contributor to muscle fatigue and discomfort. Simple changes, like taking a brisk walk during your lunch break, doing a quick home workout, or participating in recreational sports, can make a big difference. These activities allow your core to function as intended—supporting movement and stability—rather than being locked in a static, overworked state.

By prioritizing physical activity, you help your body recover from the demands of desk work, reduce muscle fatigue, and build a foundation for better posture and long-term health.

Maintaining a Healthy Lifestyle Beyond the Desk

Supporting your core and reducing muscle fatigue doesn’t end when you leave your desk. Maintaining a healthy lifestyle is key to preventing musculoskeletal disorders and promoting overall well-being. This means making time for regular physical activity, eating a balanced diet, getting enough restorative sleep, and managing stress effectively.

Incorporating self-care practices like meditation, yoga, or simply spending time with loved ones can also help your body recover from the physical and mental demands of daily life. Small changes—such as taking the stairs, walking to work, or doing household chores—add up to more movement and less sedentary behavior throughout your day.

By embracing these healthy habits, you not only reduce the risk of chronic pain and muscle fatigue but also enhance your quality of life, both at work and beyond.

Sitting Doesn’t Have to Be a Core Workout

Sitting should not feel like sustained effort. It should not require constant self-correction, muscular bracing, or ongoing awareness just to remain upright. Unlike intentional core exercises, which are designed to activate and strengthen specific trunk muscles through controlled movement and resistance, unsupported sitting places a passive and often fatiguing demand on the core without the benefits of targeted muscle engagement.

When ergonomic sitting posture is supported properly, the role of the core shifts. Instead of compensating for missing structure, it assists posture naturally—providing stability when needed, without remaining under continuous strain. The spine is able to stay aligned through external support rather than force, reducing the need for ongoing muscular engagement.

As a result, sitting begins to feel noticeably lighter. The body expends less energy maintaining posture, and discomfort is less likely to accumulate over the course of the day.

Even small improvements in how you are supported while seated can significantly reduce the physical demands placed on your body. Over time, these changes make sitting not only more comfortable, but far more sustainable. For those experiencing core fatigue from prolonged sitting, incorporating targeted exercise programs—such as core stabilization routines and trunk muscle exercises—can help address muscle fatigue and improve postural stability.

When Your Body Is Supported, Your Core Can Relax

If your core feels overworked during the workday, it is not a reflection of poor discipline, inadequate strength, or a personal shortcoming. It is a signal from the body that something in the environment is requiring unnecessary compensation.

When adequate support is missing, muscles are forced to take on roles they were never designed to perform for prolonged periods. The core, in particular, works continuously to preserve stability and protect the spine. This added workload is not sustainable—and over time, it leads to fatigue and discomfort. Interventions aimed at reducing core fatigue and improving comfort, such as ergonomic adjustments and targeted exercise programs, can help address these issues.

Restoring proper structure changes this dynamic. When the body is supported appropriately, muscles are free to return to their intended role: assisting movement, responding to change, and providing stability when needed—not replacing the function of furniture or posture aids. Additionally, recovery modalities like trunk stabilization exercises, foam rolling, or passive recovery can help restore muscle function after prolonged sitting.

With the right support in place, sitting no longer feels like something to endure or push through. It becomes a posture that the body can maintain comfortably and consistently, allowing you to focus on your work rather than managing discomfort.